“It’s not the will to win that matters – everyone has that. It’s the will to prepare to win that matters.” – Paul “Bear” Bryant

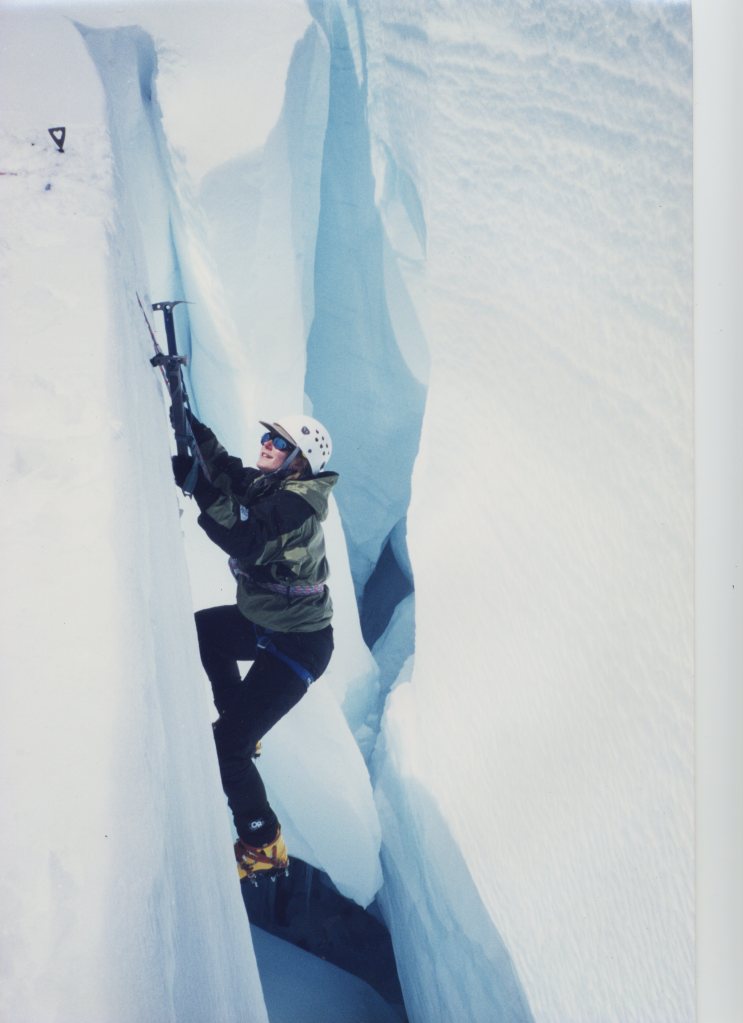

I wasn’t a particularly athletic or outdoorsy kid. It wasn’t until my late 20’s that the climbing bug bit me. I was driving my car to work. I came around a corner, saw Mt. Rainier dominating the skyline and thought, “I should climb that.” From there climbing became not only one of my passions but also in many ways my metaphor for tackling the challenges of life.

Summits, blisters, carrying a pack, one step at a time, working as a rope team, objective versus subjective dangers – all of it gave me such great perspective on life.

Give me a pebble in my shoe and I’ll turn it into an essay about self-care. I’ve failed to take the time to stop to get rid of something little before it gets big enough times to have a lot to say about that lesson.

All of this to say that I came to hiking and climbing mountains as an adult. So when I proposed to my kids in mid-December that we climb Tiger Mountain on New Years Day and they enthusiastically said they wanted to, I had to think carefully about how to make it a good experience for them.

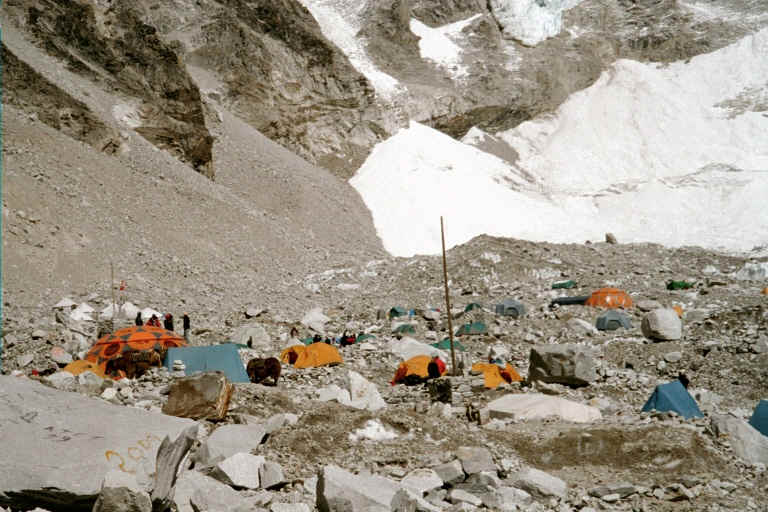

Go ahead and groan now because here comes the point cloaked in a climbing story. The first time that I tried to climb Mt. Rainier, it hurt like hell. We made it to our base camp at 10,000 feet and then a storm came in. We couldn’t leave for our summit bid at midnight as planned because it was still snowing so at 6am, the lead guide came in and said, “Whoever wants to try for the top can go ahead and gear up. But we’ll have to go twice as fast as our normal pace to get this done in half the time.”

My friends and I made it 11,000 feet before dropping out. Only 3 out of the 24 climbers made it to the top that day.

And I learned that the better shape you are in, the more fun you’ll have climbing. There are two levels of readiness – the first is to get yourself up (and down) a mountain. The second is to train enough to climb the mountain AND have some more in the tank in case you need to do a little more. It’s more likely to be fun if you’ve trained to the second level.

This applies to other things as well. Like getting ready for a presentation. The first level accounts for doing the preparation of putting together the slide deck. The second is doing that, practicing the presentation out loud, preparing the Q&A, and doing it well enough in advance to have a cup of tea to calm the nerves before starting. I’ve done that both ways as well and the second one is way more fun.

Circling back to inviting my kids along for a hike up Tiger Mountain, I wanted them not only to be able to do it but also to have fun. That meant that we all had to do the work to train to that second level. Working out on the stairs in our home, going to the Capital Hill stairs to train, walking the trail at Discovery Park, doing a pre-NY day hike up Little Mt. Si – I tried to vary it and make it fun. We had some bad moments along with the good but ten-year-old Miss O and six-year-old Mr. D were pretty good sports about it all.

I told my friend, Bill, that we’d done the hike and he sent me the Bear Bryant quote for this post. It matches what I’ve experienced. There are a lot of things we can white knuckle and get through. Having fun doing it requires some preparation.

(featured photo is the kids and I on a training hike)

You can find me on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/wynneleon/ and Instagram @wynneleon

Please check out the How to Share podcast, a podcast celebrates the art of teaching, learning, giving, and growing!