“Only those who attempt the absurd can achieve the impossible.” – Albert Einstein

When I trekked to Everest base camp in 2001, we flew a fixed wing aircraft from Kathmandu to a dusty hilltop in the Himalayas. Then a helicopter swooped in and flew us to Lukla at about 10,000 feet of elevation. And then we trekked about 30 miles to base camp from there.

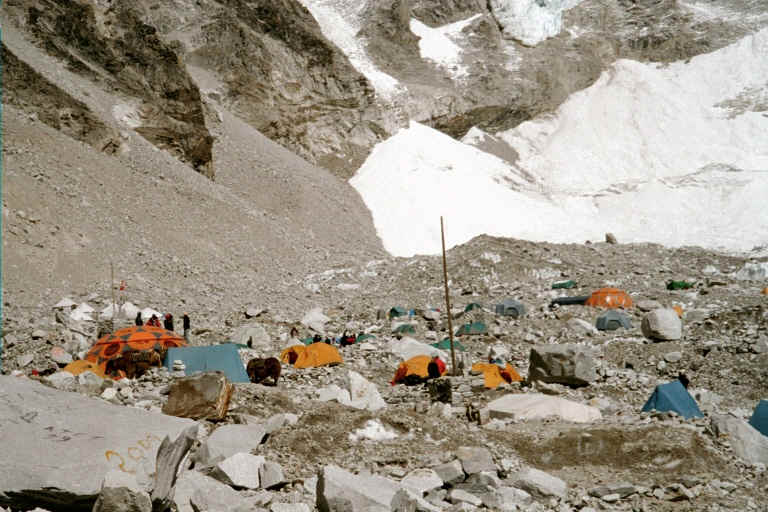

Base camp, which sits at an elevation of about 17,600 feet, was a small city with each team having a dozen or more tents around a central dining tent and communications tent.

I recently watched two Everest films. The Man Who Skied Down Everest recommended by Dr. Gerald Stein. It’s a Canadian documentary filmed in 1970 and won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1975. Six sherpa were killed during the expedition in a collapse of the Khumbu icefall.

The second was Everest recommended by Vicki Atkinson. It was a Hollywood film production released in 2015 about the 1996 Everest blizzard that killed eight people.

In the 1975 film, it took a team of 800 people to support getting the supplies the expedition needed to the mountain. But there were very few other climbers on the mountain.

In the Everest film, they got to the mountain much like I did and there were so many more climbers. Teams tried to organize the summit attempts so that climbers weren’t slowed down and freezing while waiting for their turn at choke points like the Hillary Step. In that film, they attributed the change in the number of climbers to Rob Hall, the incredibly infusive and strong guide from New Zealand who died in the storm, being willing to guide amateur climbers up Everest.

In a lot of climbing circles, it’s believed the trend actually started when Dick Bass (who owned Alta ski resort in Utah) and Frank Wells (who was President of Disney) dreamed up the project to climb the tallest peak on each continent, The Seven Summits. Dick and Frank then they hired people like my friend, Phil, to guide them up the mountains.

Regardless, there is no doubt there are challenges climbing Everest today that come from overcrowding and general human behavior like selfishness, ego, and disregard for nature. It’s not hard to imagine the Everest challenges as a fitting allegory about our world overall.

Thankfully, there are also heroes in the story.

When Beck Weathers needed to be helped down the mountain, filmmaker David Breashears and climber Ed Viesturs tied him in between them and basically walked him down as far as they could. David and Ed were up there along filming an IMAX film with Jamling Norgay, the son of the Tenzing Norgay. Tenzing was the Sherpa that successfully achieved the first ascent of Everest with Edmund Hillary.

I am in awe of the filmmakers who capture this incredible climbing footage. In an interview, I heard David Breashears describe how he practiced loading the IMAX film in a special cold room. He had to do it without gloves on because a speck on that film would look enormous on an IMAX screen. Each roll of film only captured 90 seconds of footage.

Filmmakers like David Breashears and Jimmy Chin (Free Solo and Meru), do all the work to film it, manage the extra weight, and execute their creative artistry while they are also doing the hard work of climbing. When they do it well, they make it easy to forget that they are climbing too.

In 1996, when the blizzard hit, the IMAX team was at base camp. They’d seen the crowds and had decided to delay their summit bid. When they heard that people were in trouble and dying, David Breashears told rescuers they could take any of the IMAX team supplies like oxygen tanks, batteries, and food stashed on the upper mountain they needed.

After David and his team offered their supplies and helped evacuate injured climbers, they still managed to summit Everest a couple weeks later and complete their project, albeit with very heavy hearts. The resulting movie Everest (same title as the film above but released in 1998) is the highest-grossing IMAX film.

I was writing this post about the differences on Everest from these two movies when I learned that mountain-climber Lou Whittaker died at age 95. So I switched to writing the post, The Lingering Effects of One Good Person. In the process, I learned that David Breashears also died in March of natural causes. He was 68-years-old. In recent years, David Breashears started Glacier Works, a non-profit highlighting changes to Himalayan glaciers.

(featured photo is mine of Everest, the dark peak in the back)